Essential Git Commands: From Beginner to Expert

In this Git command guide, we will explore the essential concepts necessary to master the most widely used version control tool. While most developers are familiar with basic commands, we will delve into real-life scenarios where utilizing Git’s advanced features can save time, solve complex issues, enhance your workflow, and ultimately make you a confident and expert Git user.

- Introduction to Git

- Key Concepts of Git

- Basic Git Commands

- Managing Branches and Merges

- Rebasing and Reviewing History

- Version Control with Git

- Advanced Scenarios for Manipulating Git History

- Conclusion

Introduction to Git

Git was developed by Linus Torvalds in 2005 to address the specific needs of the Linux kernel development. At the time, existing version control systems were slow and inefficient in managing a project of the size and complexity of the Linux kernel. Thus, Torvalds set out to create a tool that was fast, distributed, and capable of effectively handling parallel development branches.

Since then, Git has become the de facto version control tool in the software development industry. Its flexibility, speed, and power make it an essential choice for collaborative development teams.

Installation

If you haven’t already, refer to the following page to install Git: https://git-scm.com/downloads.

Key Concepts of Git

Git is built on several key concepts that make it powerful and flexible. Understanding these concepts will help you grasp how Git works and use it effectively.

Commit

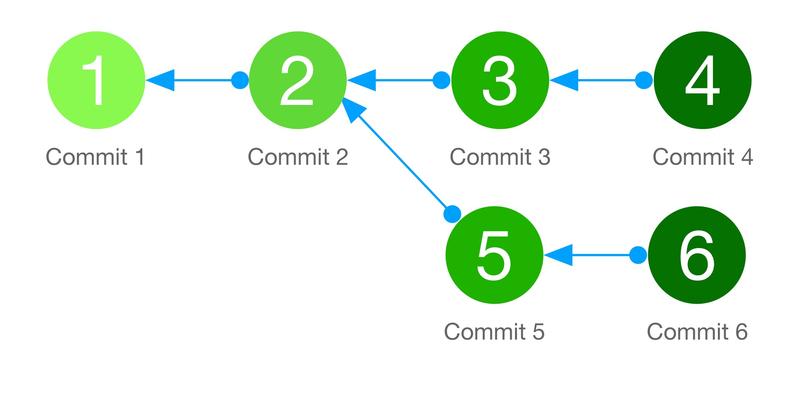

The commit is the central element of Git. It records a complete snapshot of the changes made to your code. From Git’s perspective, the history of your code is a series of interconnected commits, as depicted in the following representation:

- Each commit references the previous commit.

- It only stores the delta compared to the previous commit.

- This delta can include file modifications as well as file additions, moves, or deletions.

The commit is the visible part of Git’s internal representation structure. Note that there are other objects used by Git to store code changes, but from our perspective as Git users, the commit is the object we interact with.

Hash

- When you make a commit, Git creates a unique identifier for that commit, commonly known as a “hash” or “SHA”.

- This hash is based on the content of the commit, including file modifications, the author, the commit message, and other metadata.

- It serves to uniquely identify the commit within the project’s history.

Here’s an example of commit display, showing their respective hashes at the beginning of each line:

8634ee6 (HEAD -> main, origin/main, origin/HEAD) feat: Adds dark theme 🖤 (#32)

aae8242 fix: CSS on phones

d9bb54f refacto: Big CSS uniformization and refacto 🌟

4c77908 refacto: Tags, search results, and animation on articles (#31)

fec3121 refacto: Adjusted image size, cropping, and resolution 📺

cd6a213 fix: GitHub Actions error RPC failed; HTTP 408 curl 18 HTTP/2 (#29)Branches

Git commits allow you to track your project’s history in a clear and structured manner. However, they also enable you to work on different lines of development in isolation, which is referred to as branches.

Let’s see how branches are visualized within a commit history:

- We can observe that the sequence of these commits forms 2 branches, allowing you to work on multiple features or fixes simultaneously.

- We will explore how Git reconciles these branches using commits later on.

Best Practice

Regular and meaningful commits are a recommended practice with Git. This helps maintain a clear history, facilitating collaboration, debugging, and tracking changes. Commits serve as a form of documentation for the evolution of your project, aiding developers in understanding the history of changes and reverting to previous states if necessary.

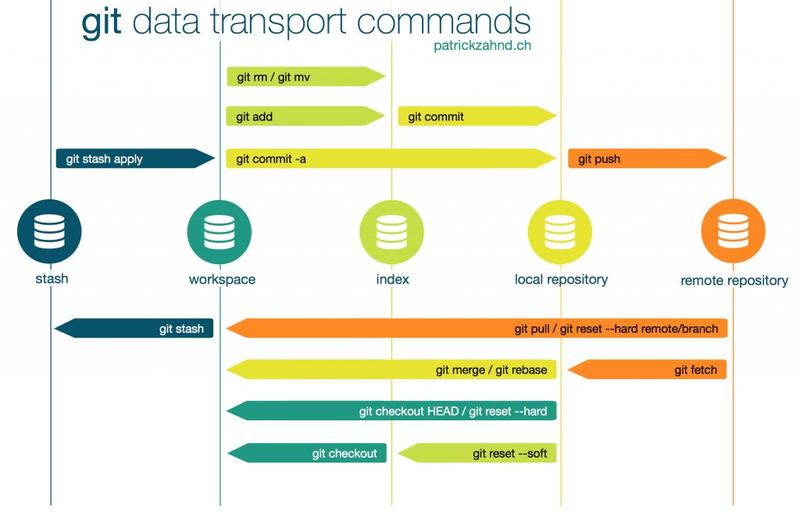

Different Git Spaces

The last concept to understand is the spaces within Git. A space is a specific working area where Git stores the different versions of your project’s files. Understanding this concept will help you know which command to apply and in what situation, whether it’s managing ongoing changes, preparing commits, or navigating between different versions of your code.

Let’s explore the 5 spaces managed by Git:

Stash or Stash Area:

The stash area is a special place where you can ask Git to temporarily store changes from your working directory. The stash area provides flexibility to switch to another branch, work on a different task, or perform tests without creating a commit.

Workspace or Working Directory:

The workspace is the directory where you work on your files. It contains the current versions of the files and is modified as you make changes to your code.

Index or Staging Area:

The index is an intermediate space between the workspace and commits. It acts as a staging area where you select specific changes to include in the next commit.

Local Repository:

This is your local repository where Git stores the complete history of your project, including all the commits, branches, tags, and configuration information. It is the local copy of your Git source code, on which you work and perform versioning operations.

Using the local repository allows you to perform operations independently, without the need for a network connection, before synchronizing with remote repositories if necessary.

Remote Repository:

The remote represents a remote repository where you can store your code, such as a Git repository on a hosting platform like GitHub or GitLab. The remote is used to facilitate collaboration with other developers, share your code, and synchronize changes among team members.

By understanding these concepts, you will be able to navigate your project’s history more effectively, organize your work with branches, prepare your commits with the index, and collaborate with other developers using remotes.

Basic Git Commands

Now that we understand the concepts of Git, let’s dive into the basic commands that will help you effectively manage your source code.

Creating a Git Repository with git init or git clone

Scenario 1: Your project is not yet under Git version control:

To start using Git in your project, you need to initialize a repository. This is done using the

git initcommand in the root directory of your project. For example:

cd /path/to/my_project

git initScenario 2: Your project is already in a remote Git repository:

Most of the time, a remote repository already exists, and you want to download it to your local machine. You can do this by running

git clone <REPO URL>to clone the repository to your local machine.

cd /path/to/a_directory

git clone https://github.com/progit/progit2.gitAdding Files with the git add Command

Once you have initialized a Git repository, you can add files to Git’s index using the git add command. This allows Git to track the changes in these files. For example, to add all modified files in your working directory to the index, you can run the following command:

git add .Recording Changes with git commit

Once you have added the files to the index, you can save the changes by creating a commit using the git commit command. Each commit represents a snapshot of the state of your project at a given point in time. For example, to create a commit with a descriptive message, you can use the following command:

git commit -m "Add new feature..."Using git stash to Temporarily Set Aside Changes

Sometimes, you may have unfinished changes in your working directory, but you need to quickly switch to another task or branch. In such cases, you can use the git stash command to temporarily set aside your changes. For example:

git stashThe above example stashes your changes in a temporary area called the stash. Once your changes are “stashed away,” you can switch to another task or branch.

Now, let’s say you have finished that task and want to resume your “stashed away” changes. You can apply them to your working directory using the git stash pop command. This command automatically applies the latest stash and removes it from the stash list. For example:

git stash popThis command applies the latest stash and restores your changes to your working directory. You can now continue working on your previous changes.

Using git stash and git stash pop allows you to temporarily set aside your ongoing changes and easily reapply them when you’re ready to come back to them. This provides valuable flexibility when managing tasks and development branches.

Managing Branches and Merges

One of the powerful features of Git is its ability to manage parallel development branches. Branch and merge management is a key skill to acquire for efficient development.

Let’s see how Git facilitates this management.

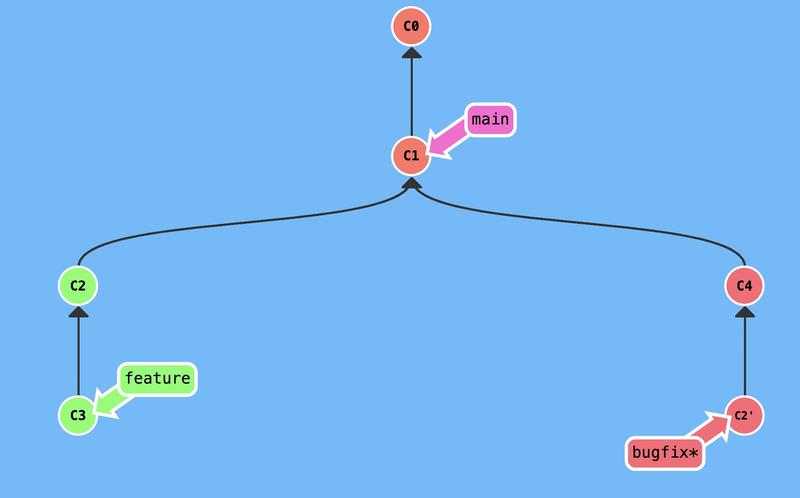

Spoiler Alert

At the end of this article, I recommend a great tool for practicing Git commands while visualizing branch and commit actions. The following screenshots are actually taken with this tool https://learngitbranching.js.org/.

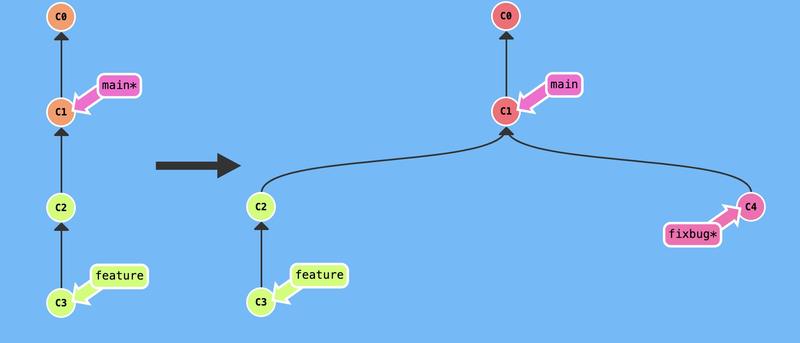

Creating Branches with git branch and git checkout

- You can create a new branch in your Git repository using the

git branchcommand. For example, to create a branch named “feat/new-functionality,” you can execute:

git branch feat/new-functionalityTo switch to this new branch, you will use the git checkout command. For example:

git checkout feat/new-functionalityYou are now on the “feat/new-functionality” branch and can start making changes specific to this feature.

- Another quicker way is to use the

git checkout -bcommand, which creates the branch and switches to it in one step after creating it:

git checkout -b feat/new-functionalityMerging Branches with git merge

When you have finished developing a feature or fixing a bug in a branch, it’s time to merge those changes with another branch, often the main branch (e.g., main or master). This is where the git merge command comes into play.

To merge one branch into another, you can use the git merge command, specifying the branch you want to merge. For example, to merge the “feat/new-functionality” branch into the main branch, you can use the following command:

git checkout main

git merge feat/new-functionalityGit will automatically attempt to merge the changes from the specified branch into the current branch. If conflicts arise, Git will inform you, and you will need to resolve those conflicts manually.

Resolving Merge Conflicts

When there are conflicts between the changes made in the branches being merged, Git cannot automatically resolve those conflicts. In such cases, you will need to manually resolve the conflicts.

Git will mark the conflicting areas in the affected files, allowing you to see the differences and choose which modifications to keep. Once you have resolved the conflicts, you need to add the modified files to the index using git add and then commit to finalize the merge.

Deleting Merged Branches

After merging a branch and verifying that the changes have been successfully integrated, you can delete the merged branch to keep your project history clean.

To delete a merged branch, you can use the git branch command with the -d option followed by the branch name. For example, to delete the “feat/new-functionality” branch after its merge, you can execute:

git branch -d feat/new-functionalityUsing git cherry-pick to Apply Specific Commits

Sometimes, you may need to apply only certain commits from one branch to another. In such cases, you can use the git cherry-pick command. For example, to apply the commit with the hash “abcdef” to the current branch, you can execute:

git cherry-pick abcdefThis will apply the specified commit to the current branch, creating a copy of the commit on that branch.

Resetting a Branch with git reset

If you need to go back to a previous state of your branch, you can use the git reset command. For example, to reset the current branch to a specific commit, you can execute:

git reset <commit>This will bring your branch back to the state of the specified commit, discarding all subsequent commits (note that the commit is not deleted).

Reverting Changes with git revert

If you want to undo one or more specific commits while keeping a record of that undo in the history, you can use the git revert command. For example, to revert the last commit, you can execute:

git revert HEADThis will create a new commit that undoes the changes made by the previous commit.

Branch management is a key feature of Git, allowing you to work efficiently on different features or fixes in parallel. The git branch, git checkout, git cherry-pick, git reset, and git revert commands provide the necessary flexibility to manage branches and changes optimally.

Rebasing and Reviewing History

Rebasing is an advanced feature in Git that allows you to modify the commit history. In this section, we will explore rebasing along with other useful commands for examining and navigating your repository’s history.

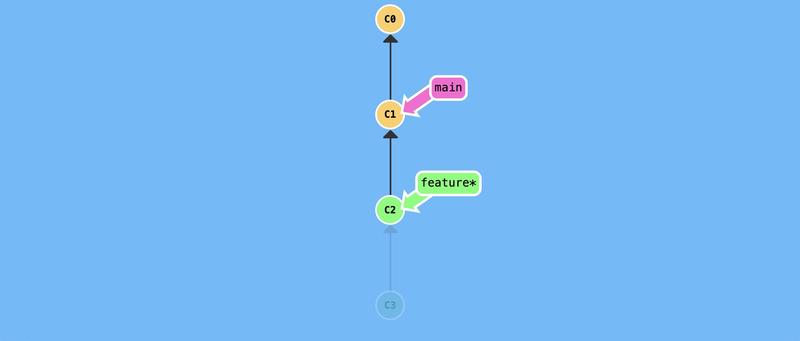

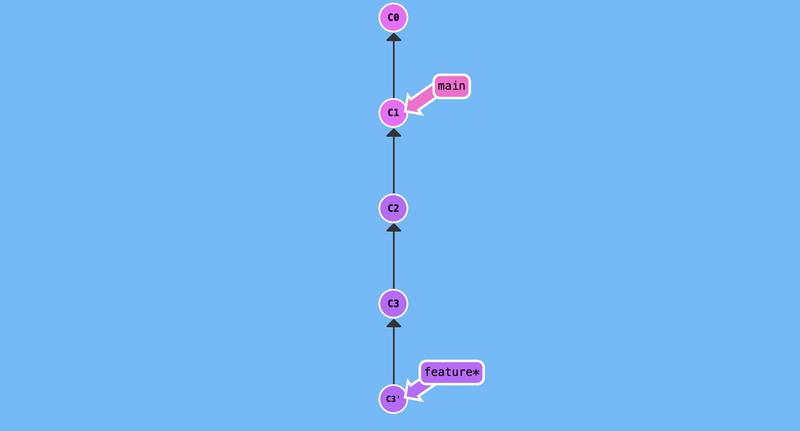

Understanding Rebase and Using git rebase

Rebasing allows you to rearrange commits in your branch, either by placing them onto another branch or by reorganizing them in a linear manner. This can be helpful in maintaining a clean and easy-to-follow commit history. To perform an interactive rebase, use the git rebase -i command. For example:

git rebase -i <destination-branch>This command will open an editor with a list of commits that you can rearrange or modify as needed:

Rebase to swap C3 and C4 of the feature branchExploring Commit History with git log

- The

git logcommand allows you to examine the commit history of your repository. By default, it displays essential information such as the author, date, and commit message. For example:

$ git log

commit 8634ee6a55086f6cf4ff7fa0ee4bbceb283d7c2c (HEAD -> main, origin/main, origin/HEAD)

Author: Jean-Jerome Levy <jeanjerome@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Thu May 25 23:54:03 2023 +0200

feat: Adds dark theme 🖤 (#32)

commit aae82424db11ad31a6aba2cb0c27a264e177b9a1

Author: Jean-Jerome Levy <jeanjerome@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Wed May 24 20:41:20 2023 +0200

fix: CSS on phones

commit d9bb54f71bd3bf609cfd6ccfcfdd8df14bf5f06b

Author: Jean-Jerome Levy <jeanjerome@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Tue May 23 22:59:36 2023 +0200

refacto: Big CSS uniformization and refacto 🌟

...This command displays a detailed list of all commits, from the most recent to the oldest, allowing you to track the evolution of your code.

- You can format the log output to display only the information you are interested in. For example, to have a compact display, enter

git log --oneline:

$ git log --oneline

8634ee6 feat: Adds dark theme 🖤 (#32)

aae8242 fix: CSS on phones

d9bb54f refacto: Big CSS uniformization and refacto 🌟

...git and vi

Git uses vi as the default text editor. Here are some commands to keep in mind:

ESC : qto exit,ESC : ito edit,ESC : xto quit and save,ESC : s/x/y/gto replace all occurrences of x with y.

Using the HEAD Pointer to Navigate History

The HEAD pointer is a special pointer that refers to the current commit in your repository. You can use it to navigate through the commit history. For example, to display the details of the current commit, you can execute:

$ git show HEAD

commit 8634ee6

a55086f6cf4ff7fa0ee4bbceb283d7c2c

Author: Jean-Jerome Levy <jeanjerome@users.noreply.github.com>

Date: Thu May 25 23:54:03 2023 +0200

feat: Adds dark theme 🖤 (#32)

diff --git a/_includes/head.html b/_includes/head.html

index bf20ecf..2c3823d 100755

--- a/_includes/head.html

+++ b/_includes/head.html

@@ -109,6 +109,9 @@

font-display: swap;

src: url("/assets/fonts/nunito-regular.woff2") format("woff2");

}

- </style>

+ </style>

+ <script>

+ localStorage.getItem('darkMode') === 'true' && document.documentElement.setAttribute('data-mode', 'dark');

+ </script>

...This command will display detailed information about the current commit, including the modifications made.

Special Operators ^ and ~ for Referencing Specific Commits

The ^ and ~ operators allow you to reference specific commits using relative notations.

For example:

^refers to the parent commit (the previous one).~refers to the commit preceding the parent (the second-to-last one).

For instance, to display the details of the direct parent commit of the current commit, you can use:

git show HEAD^These operators are useful for quickly navigating through the commit history without having to know their exact identifiers.

Rebasing and reviewing history are advanced features of Git that enable you to manage and structure your commit history effectively. The git rebase, git log, HEAD^, and HEAD~ commands provide you with the necessary tools to explore, manipulate, and understand your Git repository’s history.

Version Control with Git

One of the fundamental aspects of Git is its version control system, which allows you to manage different versions of your project effectively. In this section, we will explore commands for comparing differences between versions, retrieving previous versions, and managing remote branches.

Comparing Differences with git diff

The git diff command allows you to visualize differences between versions of the source code. For example, to display the modifications between the current state and the last commit, you can execute:

$ git diff HEAD

diff --git a/_posts/2023-05-28-tuto-git.markdown b/_posts/2023-05-28-tuto-git.markdown

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..22b5ca1

--- /dev/null

+++ b/_posts/2023-05-28-tuto-git.markdown

@@ -0,0 +1,509 @@

+---

+layout: post

+title: "Guide Complet de Git : Maîtrisez ses Commandes Essentielles"This command displays the lines that have been modified, added, or deleted between the two versions. Here, it indicates that I added a new file and provides its content.

Retrieving Previous Versions with git checkout

If you need to go back to a previous version of your project, you can use the git checkout command.

For example, to go back to a specific commit with the identifier “abcdef,” you can execute:

git checkout abcdefThis will set your working directory to the state of that commit, allowing you to work with that specific version.

Managing Remote Branches with git push and git pull

Git allows you to work with remote repositories, such as those hosted on platforms like GitHub or GitLab. To push your local changes to a remote repository, use the git push command. For example:

git push origin feat/my-featureThis command sends the changes from your local branch to the corresponding branch in the remote repository.

To retrieve the changes made in the remote repository and merge them into your local branch, use the git pull command. For example:

git pull origin bugfix/the-fixThis command retrieves the changes from the corresponding branch in the remote repository and automatically merges them into your local branch.

These commands allow you to synchronize your local repository with remote repositories, facilitating collaborative work and version tracking.

Advanced Scenarios for Manipulating Git History

In this tutorial, our main goal is to teach you how to handle the cases we will discuss in this chapter. You will apply the concepts we have just explored to manipulate commit history and solve complex problems that developers often encounter in their projects.

By acquiring these skills, you will become an experienced developer, distinguishing yourself from those who rely solely on basic Git commands.

How to Rewrite Multiple Commits into One?

To rewrite multiple commits into one, you can use the git rebase -i <commit> command, where <commit> is the commit prior to the ones you want to rewrite.

Here are the steps to follow:

First, use the

git log --onelinecommand to identify the number of commits you want to rewrite into a single one by counting the last commit.Once you have identified the number, proceed with the rebase. For example, if you want to rewrite the last three commits, use

git rebase -i HEAD~3. This will open the default text editor with a list of commits to be rewritten.In the text editor, replace the word

pick(orp) withsquashor simplysfor the commits you want to merge into one. For example, if you have three commits and you want to rewrite them into one, you will modify the second and third commits usingsquashors. Again, knowledge of vi commands can make this task easier:ESC : s/p/s/gSave and close the text editor (via the vi command

ESC : x). Another editor window will open, allowing you to modify the message of the final commit. You can keep the message from the first commit or modify it as needed.Save and close this editor window as well. Git will then perform the rebase and merge the selected commits into one commit.

Make sure you understand the implications of rebasing, as it modifies commit history. If you have already pushed these commits to a remote repository, you will need to perform a git push --force to update the remote repository with the rewritten history.

Note that rewriting shared history can have consequences for other developers working on the same project.

Caution

- It is important to communicate with your team and follow best collaboration practices when rewriting commits.

- In general, it is recommended to proceed this way when working alone on your branch.

Modifying the Message of a Commit

Sometimes you may commit with an incorrect, incomplete, or poorly formatted message. In such cases, Git provides a simple solution to modify the message of a previous commit. Here’s how to do it.

Modifying the Message of the Last Commit

- Use the

git commit --amendcommand followed by the-moption and the new message you want to use:

git commit --amend -m "New commit message"This will modify the message of the last commit using the specified new message.

Modifying the Message of an Older Commit

- If you want to modify the message of an older commit, you can use the

git rebase -i <commit>command, where<commit>is the commit prior to the one you want to modify.

git rebase -i HEAD~3In the text editor that opens, replace “pick” with “reword” or simply “r” in front of the commit you want to modify the message for. This will open the text editor with a list of commits. Modify the word “pick” to “reword” or “r” in front of the appropriate commit, then save and close the editor.

Once you have modified the commit message, save the changes and close the editor. Git will then perform the rebase and allow you to modify the message of the selected commit.

It’s important to note that if you have already pushed the commit you are modifying the message for to a remote repository, you will need to perform a git push --force to update the remote repository with the new message.

The ability to modify the message of a previous commit allows you to correct errors or improve the clarity of messages for a more accurate and informative commit history.

Caution

- Make sure to communicate with other developers working on the same project, as this can affect their commit history.

- In general, it is recommended to proceed this way when working alone on your branch.

Modifying Files in a Previous Commit

There may be cases where you need to modify files in a previous commit in Git. This could be due to content errors, forgetting certain files, or other reasons requiring retroactive changes. While Git encourages preserving commit history integrity, there are methods to make changes to past commits.

Here are some steps to modify files in a previous commit:

Use the

git rebase -i <commit>command, where<commit>is the commit prior to the one you want to make changes to. This will open the text editor with the list of commits in reverse chronological order.Locate the commit you want to modify and replace the word “pick” in front of that commit with “edit”. Save the changes and close the editor.

Git will then perform the rebase and pause the process after applying the commit you want to modify.

Use the

git checkout <commit> -- <file>command to extract the specific file version you want to modify from the previous commit. For example,git checkout HEAD~1 -- file.txtextracts thefile.txtversion from the previous commit.Make the necessary changes to the file according to your needs.

Once you have made the modifications, use the

git add <file>command to update the changes in Git’s index.Use the

git commit --amendcommand to create a new commit with the modifications. You can modify the commit message if necessary.Repeat steps 4 to 7 for each file you want to modify in this commit.

When you have finished modifying the files, use the

git rebase --continuecommand to proceed with the rebase and apply the changes.

It’s important to note that if you have already pushed the commit you are modifying the files for to a remote repository, you will need to perform a force push (git push --force) to update the remote repository with the modifications.

The ability to modify files in a previous commit allows you to correct errors or make retroactive changes when needed. However, be cautious when modifying commit history as it can lead to inconsistencies and conflicts if misused.

Caution

- Make sure to communicate with other developers working on the same project, as this can affect their commit history.

- In general, it is recommended to proceed this way when working alone on your branch.

Conclusion

We have covered the essential concepts of Git and explored a set of key commands to help you master this powerful tool. By understanding commits, workspaces, the index, stash, and local and remote repositories, you are now ready to optimize your work and make the most of Git.

If you want to further expand your knowledge of Git, I recommend checking out the following resources:

Official Git Documentation: The official Git documentation, available in multiple languages, is a reliable, comprehensive, and clear source to learn more about advanced Git features.

Learn Git Branching: A web application, with its code available on GitHub, that offers interactive tutorials and allows you to visualize the impact of a command on branches and commits in your Git repository. I recommend trying it out to test your new knowledge.

By exploring these additional resources and continuing to practice, you will be able to deepen your understanding of Git and become an expert.